Nelson Mandela tour, South Africa: How has the country changed?

I am having trouble understanding Christo Brand. It’s not the quality of the phone line. Rather, it’s his thick-as-molasses South African accent when he talks in English. I’ve been to Cape Town more than 30 times but I’m struggling.

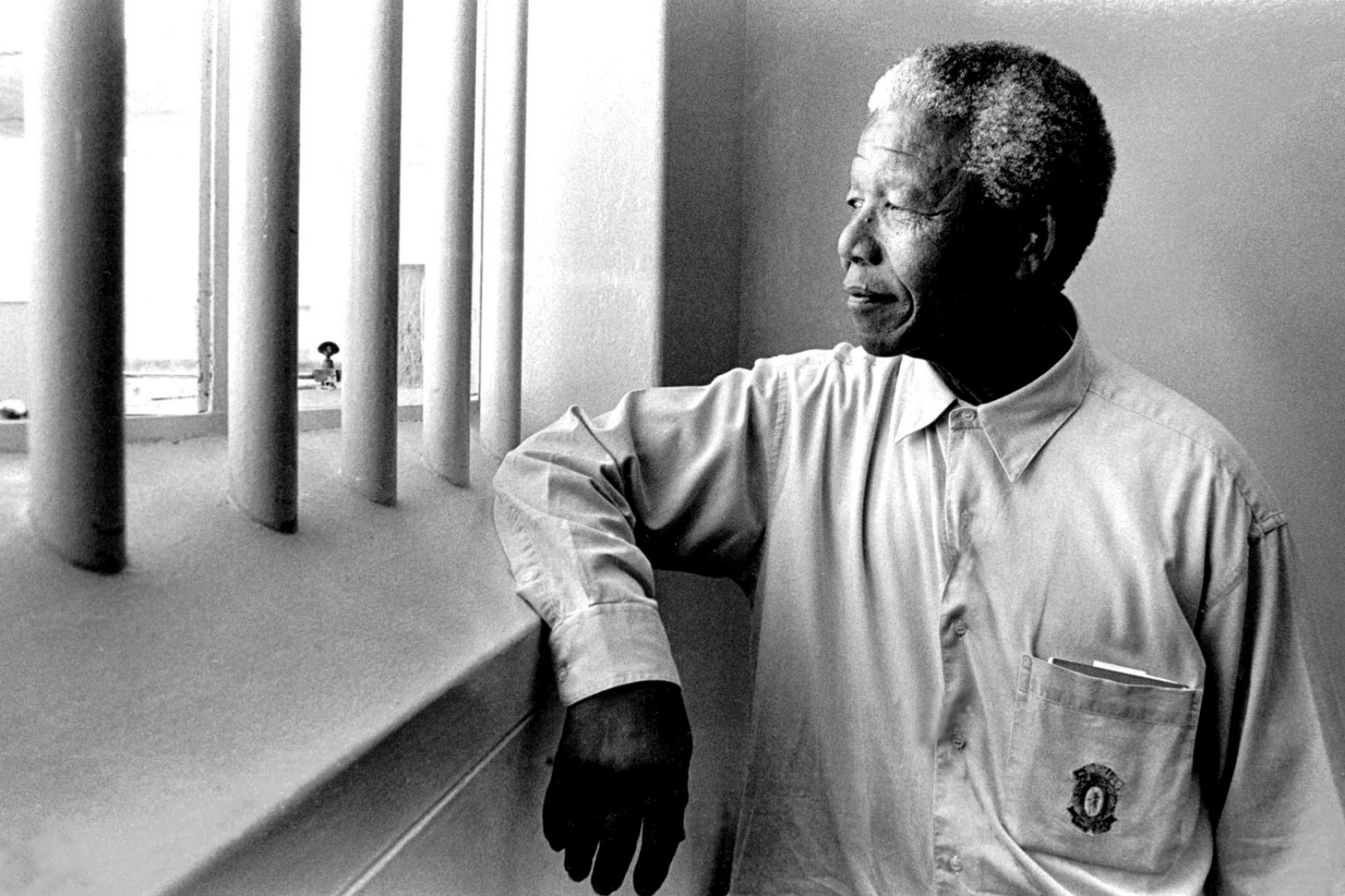

Brand is telling me about his unusual friendship with the late President Nelson Mandela – the man who was jailed for 27 years for his opposition to the National Party government’s policy of apartheid – and who was born 100 years ago this month.

Unusual? Brand was one of Mandela’s prison guards on Robben Island and at Pollsmoor Prison, both in Cape Town. He went from regarding Mandela as a terrorist to a close personal friend. He secretly arranged for the African National Congress leader to see his granddaughter in jail and sat with him in his cell on his 70th birthday watching the movie The Last Emperor.

‘I first met him in October 1978, about three months after I’d started my job on Robben Island,’ Brand recalls. ‘I was told he was the biggest terrorist in the country and we were supposed to hate him, but he was already an elderly man, and I treated him with respect.’ Brand is the author of Mandela: My Prisoner, My Friend (John Blake Publishing).

Credit: Jurgen Schadeberg/Getty Images

Robben Island, where Mandela was held from 1963 to 1982, is now an essential stop for any visitor to Cape Town. You can inspect the prison blocks and listen as former inmates act as tour guides. (Book online before you leave home: in summer it gets very busy.) Certainly, this centenary year in particular, the legacy of Madiba, as Mandela was affectionately known, acts as a lightning rod for tourism to the country and is a reason many people visit South Africa.

Away from the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront, where you board the 20-minute ferry to Robben Island, I climbed into my rented VW Golf and drove round the side of Table Mountain. The former District Six neighbourhood spread out beside me. It was once a lively, thriving area with bars and jazz joints and people of all colours mixing. Which was a problem for the pro-apartheid government. So during the 1970s, District Six was bulldozed and most of its 60,000 non-white residents moved to the dusty suburb of Mitchells Plain, out beyond the airport. If I’d continued on the M2 motorway I’d have arrived there, but I turned off, past the neat, posh, gated suburbs of Constantia and Newlands, past vineyards and cricket grounds.

I reached the golf course in leafy Tokai, but that was not my destination. Instead I turned into the gates of Pollsmoor maximum-security prison, where Mandela was incarcerated between 1982 and 1988.

It’s an unusual tourist destination, I agree, but for those who want to travel on the Mandela trail, it’s possible for anyone – once they’ve had the boot of their car inspected – to drive in, park up and eat at the prison officers’ canteen deep inside the razor-wire protected fences (still well away from hardened gang members).

Credit: Christo Brand; Victor Verster Prison; Cape Town Tourism

The food isn’t going to win awards: but it’s cheap. Your waiters are low-risk prisoners awaiting release and being trained for a vocation that will hopefully keep them on the straight and narrow. I was here for breakfast: fried eggs, sausage, bacon, toast. You’re not supposed to ask why people are incarcerated but I couldn’t resist. ‘Bad chicks,’ I was told by my server, who was missing a few teeth. ‘Problems with women?’ I responded. ‘Nah man,’ he replied in heavily accented South African English, where vowels are swallowed up and flung about with abandon. ‘I was writing bad cheques… they bounced.’

Drive east for around 45 minutes and mountains start to rear up in front of you. Before you reach them, signs for wineries become prolific. Many vineyards offer tastings and have restaurants and cafes, as well as tree-shaded lawns on which to spread out an impromptu picnic. If you turn off the motorway near Paarl and head towards the foodie village of Franschhoek, the driveway of the Drakenstein Correctional Centre might look familiar.

It was from here that Mandela walked to freedom on 11 February 1990, when it was known as Victor Verster Prison. With a bit of planning you can go inside to see the cottage where he spent the last few months of his captivity; you just need to call and ask for the communication manager with at least two weeks’ notice.

So I got to sit on Mr Mandela’s toilet, although I thought it would have betrayed the dignity of the place to take a selfie. And I was shown the holes drilled in the barbecue outside where the security services planted their bugging devices. It was all in all a very ordinary brick bungalow… if you ignored the guards and the barbed-wire fence.

Credit: Cape Town Tourism

In Johannesburg, some 1,400 kilometres away from Cape Town, there is an unofficial Mandela trail that you can follow, reflecting Madiba’s life here both before and after his long incarceration.

Joburg – aka Jozi or Egoli, its Zulu name – has found it hard to shake off its gritty reputation. But it’s a place I love, that pulses with creativity and energy. I always have a great time there as long as I place myself in the hands of a good guide, such as 34-year-old Michael Letlala from Coffee Beans Routes .

Letlala suggested heading to Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, in the north of the city, now a museum. It was once the secret headquarters of the African National Congress and a raid there by the government in 1963 led to Mandela and others being put on trial and then jailed.

He also took me to visit Sophiatown Heritage Centre. Here we were hosted by a resident on a walking tour of the area, which, in similar fashion to District Six, was a lively district that was destroyed from the 1940s onwards as the forced-removal policies of the pro-apartheid National Party took hold. Even the neighbourhood’s Chinese population was relocated to the centre of Johannesburg.

‘I think Mandela’s legacy is one of forgiveness, love and to never stop believing in your goals,’ Letlala told me as we paused in the afternoon for coffee in the trendy Maboneng Project area.

Credit: Peter Chadwick

Credit: Christopher Furling/Getty Images

A few days – including an hour’s flight and a five-hour drive – later I’m bumping along a dirt road towards the Indian Ocean, not far from Qunu where Mandela was born and where he’s buried. This is the Eastern Cape, also known as the Wild Coast. Kiss goodbye to phone signal or plug sockets to recharge the trinkets of 21st century life.

I spend five glorious days hiking with Matt Botha and his partner Camilla Howard, who run tour company Wild Child Africa . We cross rivers with backpacks held above our heads, bathe under waterfalls, rescue lost goats, get rained on, get sunburnt, scrape oysters off rocks, meet solitary fishermen and walk along empty beaches.

‘I remember in 1992,’ Botha tells me around a crackling fire one evening, ‘I was playing in an under-13s rugby team and we’d driven to a match in the Orange Free State [known today as the province of Free State] where we had to stay overnight.

‘Just as we were about to get off the bus, the team manager stood up and said to the only black player, “Sorry, you need to stay on here tonight. This hostel is for whites only.” Unfortunately we were born into a South Africa that made it acceptable to leave a teammate on a bus because of who he was. How I wish that I had stayed with him.’ He pokes at the flames with a stick and reflects silently.

South Africa is a gorgeous country whose strongest asset, I’ve always felt, is its people. As holiday destinations go, it’s hard to beat. At times, like Christo Brand’s accent, it might be hard for outsiders to fathom but locals like Botha believe it’s the most beautiful and diverse country on Earth with millions of people who, like him, love the place unconditionally. The legacy of reconciliation and peace is perhaps Mandela’s greatest gift.

Credit: Daniel Hundven-Clements/Gallery Stock/Snapper Media

How Mandela changed tourism

Since Nelson Mandela was released in February 1990, and South Africa’s apartheid policies removed, the country’s tourism industry has boomed. In the month of Mandela’s release, just 119,335 tourists visited the country. In the year before his release, there were just 1.5 million international visitors.

Twenty-eight years on, 2.61 million international visitors entered the country in March 2018 alone – and during 2017, 10.3 million arrived on South Africa’s shores. They’re staying in its 1.39 million accommodation units. In 1990, there were an estimated 1,003 hotels for visitors.

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)