Pingyao: China's unlikely centre of photography

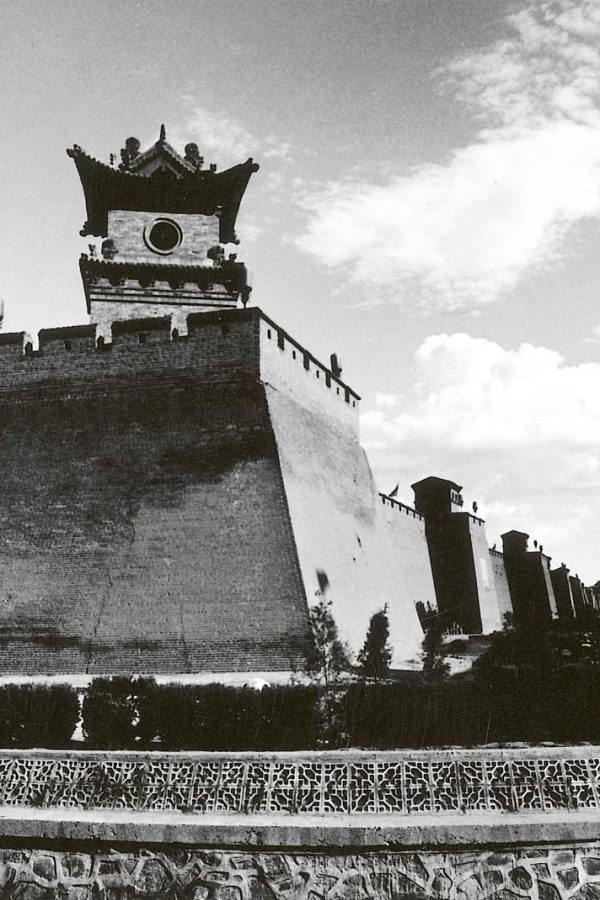

To keep their children safe at night, Pingyao elders warn of their ancestors’ ghosts wandering the streets after dark. It’s a believable story. With a towering city wall, ancient paths, and Ming- and Qing-dynasty houses, much of Pingyao has remained unchanged since China’s imperial days.

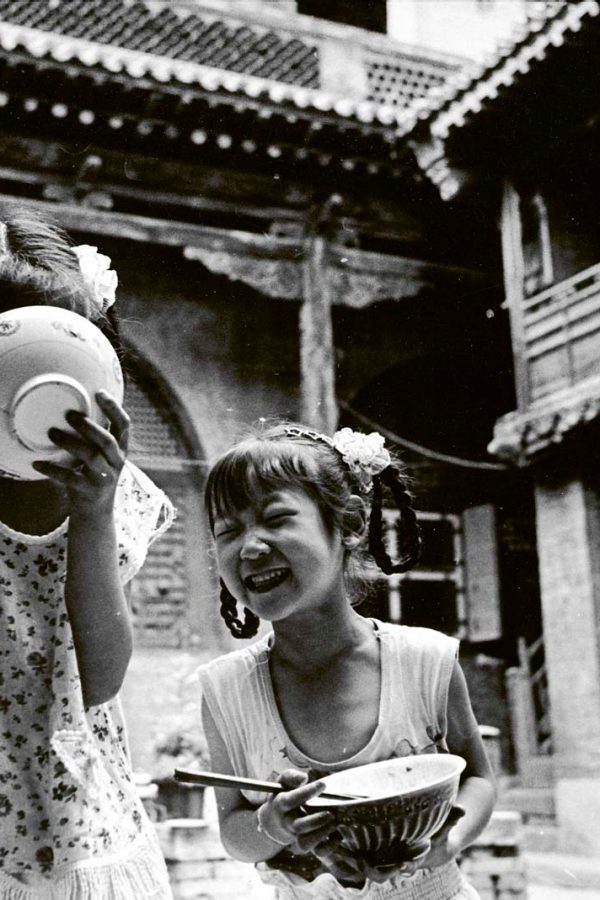

That’s the city’s attraction. By day, a stream of sightseers flows through Pingyao’s streets by bicycle or on foot. But just off the main streets locals gossip in doorways, hang out their laundry or slurp noodles doused in pungent vinegar, paying little mind to the outside world’s intrusion. As evening arrives, red lanterns illuminate the town, until about 11pm when they go dark, signalling that the night must end young. Pingyao sleeps early, as if the imperial curfew were still enforced.

‘It’s a living museum,’ says Li Zhengde, a professional photographer, while excitedly snapping photos of Qing archways and Mao-era tenements. He’s far from the only one who comes to Pingyao for its photogenic, old-world looks. Since 2001, Pingyao has capitalised on its surroundings with an event that’s thoroughly modern: the Pingyao International Photography Festival. Li is one of many notable artists who have been invited to talk or exhibit at this event over the years.

But let’s go back to the beginning. The story of how this town in landlocked Shanxi province was built up with such mesmerising architecture is told in Rishengchang, China’s original draft bank, founded in 1823, which is now a museum. It’s here that Ming-dynasty merchants evolved to become Qing-dynasty financiers. Shanxi businessmen used cheques instead of silver coins to protect monetary transactions from banditry, modernising banking in China and solidifying Pingyao’s standing as a financial centre of its time. At its zenith the bankers ran 57 branches nationwide and had clientele as far away as India.

The profits from banking were spent on fine temples and town houses, which make up today’s architectural treasure trove. Of these the City God Temple is a real highlight. It’s a sacred Taoist site that venerates, among other deities, Shui Yong, a Zhou-dynasty paragon and patron saint of Pingyao. But beyond the traditional feng shui setup – the drum and bell towers, the god of wealth shrine – it is the temple’s blue-glazed roof tiles that distinguish it from other holy sites of a similar vintage.

Pingyao’s prestige waned during the chaotic last days of the Qing period, as financial institutions introduced by the West began to take over. The relative isolation of Pingyao’s location spared it the ravages of the 20th century, yet it has only been during the past 20 years that Pingyao’s fortunes have been rekindled, this time as a tourist destination.

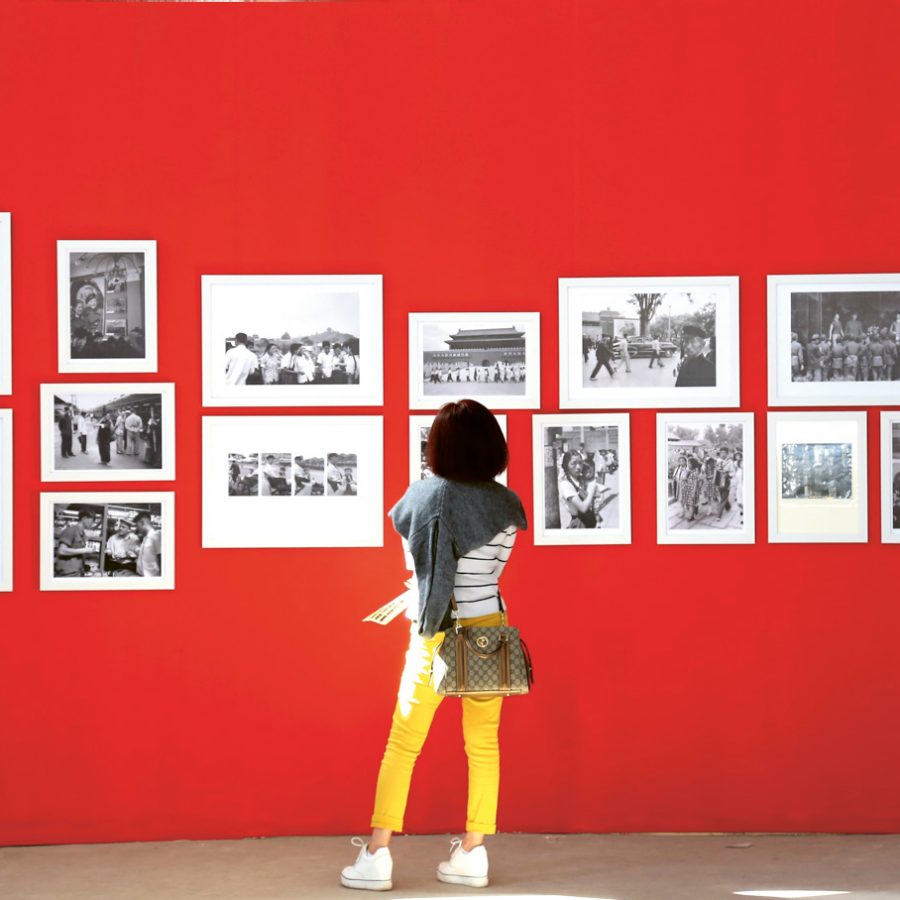

The annual photography festival has been an influential part of this revival. Every year, the event’s arrival transforms the town into an exhibition space. Using both indoor and outdoor space, the old quarters are turned into contemporary galleries. Curious art students, Beijing hipsters and photography enthusiasts point Nikons at everything and anything, infiltrating the ranks of holidaymakers. It’s certainly the biggest and longest-running photography festival in China, and one of the largest in the world.

‘I see Pingyao Ancient Town as an open stage for us to put on a show,’ says Zhang Guotian, who heads the festival. ‘We have nine exhibition spaces including two old factories. And we exhibit everyone from emerging talents to established masters, foreign artists to Chinese photographers. You know we’ve launched the careers of Mo Yi, Shi Guorui, Wang Fuchun and Zhang Jian, to name but a few.’

While Lianzhou Foto in Guangdong is arguably China’s edgiest photography festival, Pingyao is certainly the most diverse. Take the 2016 edition of PIP, as the event is called. One moment we’re enjoying an exhibition of South African female photographers, the next we’re exploring Square, a photo series by Chen Zhixian documenting an outdoor plaza over 36 years and curated by notable French-British journalist Robert Pledge. The festival features workshops and talks, too. And at night, the restaurants heave with critics and curators banqueting on Jin cuisine, which leads to spirited, alcohol-doused debates regarding photography in China.

Of course, Pingyao isn’t immune to the forces of modernisation. Many of the town’s old residences are now restaurants, antique stores or boutique guesthouses. Some have been converted into museums recalling Pingyao’s past. And the legions of tour groups try in vain to negotiate the narrow streets via the electric buggies the government has introduced in place of cars. Motor-trikes add to the traffic chaos.

But much of the ancient area remains residential and is best viewed from the mighty city wall, some 10 metres high and six kilometres in length. The ramparts are peppered with gates, six of which are crowned by watchtowers, with layers of eaves rising skyward. Walking along the wall gives the feeling of treading in the footsteps of the imperial city guard.

‘It’s changed so much, but it’s still got its charm,’ says Zhang, who first photographed Pingyao in the 1990s. ‘That’s what PIP is all about, a dialogue between the old and the new.’

Of photos and film

The Pingyao International Photography Festival has been a fixture since 2001. Its focus is on Chinese photographers and culture, but visitors and photographers come from all over the world. International stars who have exhibited here in the past include Marc Riboud, the French war photographer, and René Burri, the Swiss known for his portraits of Che Guevara. Today it is one of the world’s largest photography festivals. It takes place this year from 19 to 25 September. pip919.com

This year even more modern culture comes to the old city, with the launch of the Pingyao Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon International Film Festival. Celebrated Chinese director Jia Zhangke (A Touch of Sin) and veteran film festival organiser Marco Mueller are behind the event, which is expected to show about 40 works. It will run from 19 to 26 October. pyiffestival.com

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁�體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)