The great Mongolian open-air theatre

Imagine you’re taking a journey inside a film. Then suddenly it stops being a normal movie and switches to Imax. The screen widens, the colours intensify, the light is diamond-grade clear and every angle, every shadow stands out like the blade of a knife. The old film – the rest of the world – seems faded and blotchy in comparison.

That’s the best way I can find of describing what it’s like to be in Mongolia for the first time.

Hong Kong has its moments of bright sunshine, fresh breezes and atmospheric clarity, too. But I’d left it on one of those rather more common, squashy days when the air is an undefined state of matter somewhere between a liquid and a gas. So to look out of the car window on a piercing-blue, early autumn Mongolian day was a shock to the senses – and not just the optical one.

Our car took us out of the capital, Ulaanbaatar, west towards Bayangobi. We passed through the various economic zones – downtown retail and corporate, power plants, light industry and improvised districts with hotels for temporary workers and hilly suburbs for the managers.

Then we entered the vast, empty land and the complexity of modern work and progress disappeared in the rear view mirror. Here, in the 18th biggest country in the world and the third least densely populated, economic activity means horses, sheep, goats and camels – and the occasional human being to look after them. That’s the way it’s been for generation after generation, and despite an economic revolution elsewhere in Mongolia, that’s the way it’s stayed.

Our first stop was at an ovoo: not a sentence I’ve been required to write in the course of my travels before. But then you’re likely to notch up a whole list of firsts on your first trip to Mongolia.

An ovoo is an improvised shrine. This one was about the size of small car. Anu, our guide, asked us to pick up a pebble. We tossed the pebbles on the mound of jagged sandstone rocks. Then we walked around it three times, in the proper Buddhist manner. I stopped in an equally Buddhist manner to avoid squashing a desert gerbil as it scurried between fist-sized holes made obliquely into the sand.

You see ovoos – some as huge as temples, others no more than cairns a few feet high, some of them many centuries old – throughout the country. The Communist authorities tried to abolish ovoo-building and worship. Good luck policing that in a country where there are 1.9 people per square kilometre – and most of them live in the capital.

Each ovoo supports a weathered pole and the wires of the prayer flags: blue for sky and space, white for air and wind, red for fire, green for water, yellow for earth.

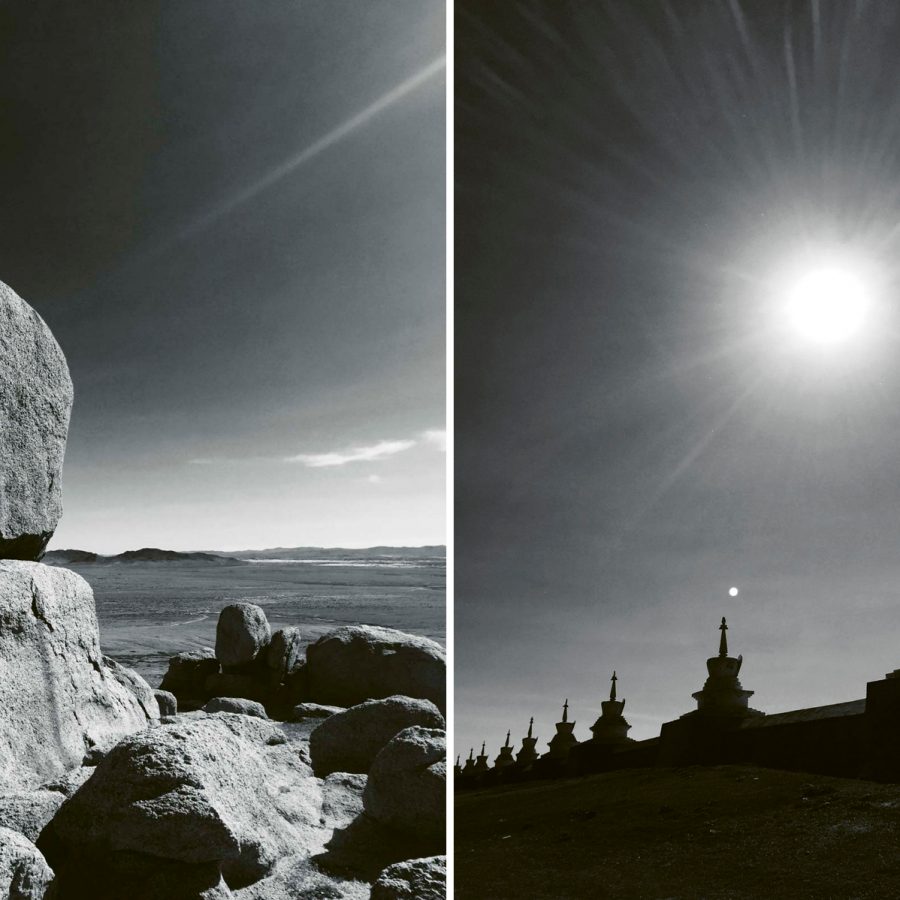

Back in the car, I thought how the landscape stretching out before us seemed elemental, too, pared back to a handful of colours, textures and shapes. As the morning wore on, only a gauzy mist covered the naked planet. The soft green hills and dark rocky outcrops were like tiny islands in a limitless ocean of grass, scrub and sand.

Credit: Tuul and Bruno Morandi / Alamy Stock Photo / Argusphoto

Credit: Luca Zordan / Gallery Stock / Snapper Media

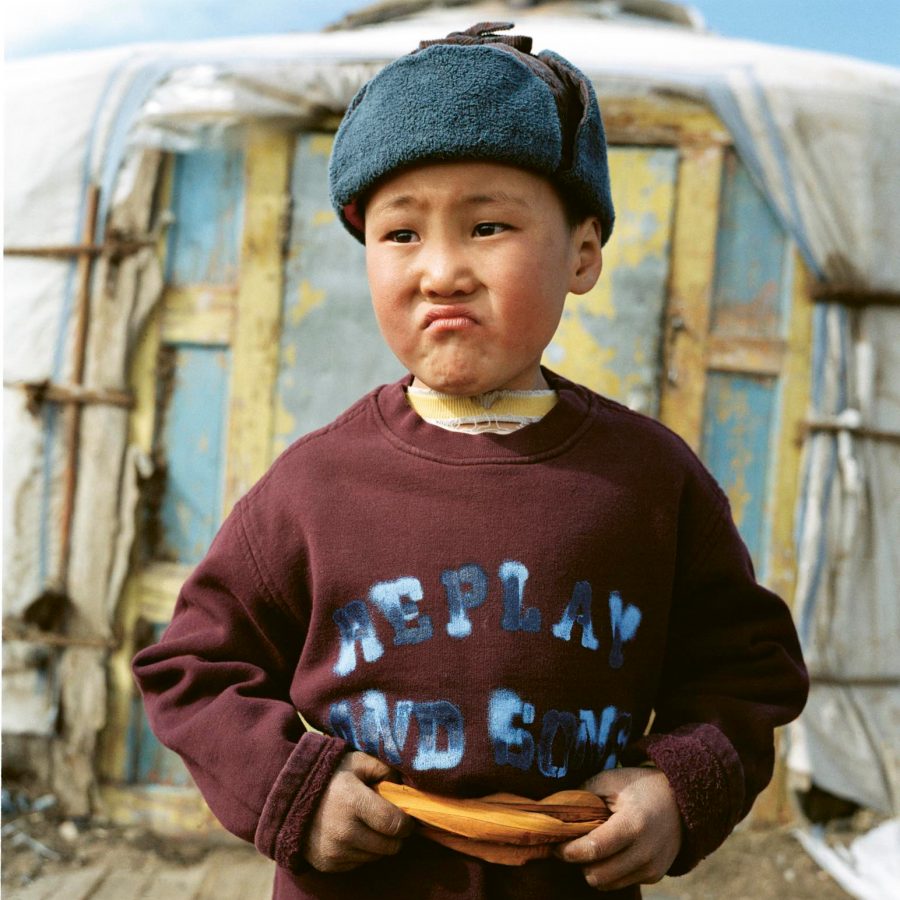

There are isolated villages, too. From a distance you think you’re heading to a music festival, with a scattering of brightly coloured tents clustered on a plain or a hill. Closer up, as the Imax camera focuses, you see they’re steep-pitched houses painted in the same bright colours as the flags. To my European eyes they looked like they’d been transported all the way from a Norwegian fishing village – and taken a bit of a battering along the way.

After a few hours, we turned off the highway and bumped softly as a speedboat across a sandy track to the Hoyor Zagal lodge.

After our long journey we ate a homely lunch of chicken, potatoes and Golden Gobi beer. The kitchen made a special effort and rustled up vegetables. We had two helpings as Anu and our driver didn’t touch theirs. Mongolians are not big fans of the green stuff. The nomads get most of the vitamins they need from mare’s milk; and urban Mongolians have not adopted the habit of consuming the flora in a big way.

Accommodation in Bayangobi – the ‘rich’, fertile area of the great desert – means, as it means everywhere in rural Mongolia, a ger. These loaf-shaped tents covered in thick felt are a miracle of construction and roomy comfort. With the suitcases stacked neatly against the walls we sat back on our beds and listened. The Imax theatre that is Mongolia also has a state-of-the-art sound system. In this acoustically perfect wilderness, we could hear a finch pecking in the grass by the next tent. A workman hammered in a wooden stake like a percussionist in a concert hall. And here and there you picked up the whiskery, soft syllables of the Mongolian language.

In the days that followed we explored the lonely Ovgon Khiid monastery and picked our way around the vast, 80-kilometre sand dune system. We hung out with a family of camel herders in their ger.

Credit: Annabel Ross Jones

Credit: Annabel Ross Jones

By necessity, Mongolian householders are interior designers of genius. Around the circular wall were modern pine cupboards, chests painted in traditional motifs, neat piles of clothes, embroideries and photographs in frames and rugs, rugs, rugs. We were enjoined not to walk between the two main poles either side of the stove: in a ger, that is akin to coming between a husband and wife.

The main site here is the ancient capital of Karakorum, near the present-day town of Kharkhorin. The city was built at the height of the Mongol empire in the mid-13th century. (There’s nothing that a dominant ruler likes to do better than create a new capital.)

Genghis Khan chose Karakorum for his capital, but it was his third son, Ögedei, who really built the city – and many others as the nomads consolidated their empire from China to Persia and the gates of Europe.

The main sight at Karakorum isn’t the city – little remains apart from the occasional giant stone turtle – but the 16th century Erdene Zuu monastery. The monastery itself has been hollowed out by war and an attempt by Mongolia’s Communist ruler to obliterate it in the 1940s. (It was saved by Russian leader Stalin for international public relations purposes.) But the outer wall, a commanding line of stupas surveying the steppe, remains; as do three magnificent temples depicting different stages of the Buddha’s life and work.

To get a feeling of Karakorum in its glory years, you need to visit the excellent onsite museum. The model of the city shows a harmonious, impeccably planned multicultural, multi-faith settlement that seems far removed from the legend of bloodthirsty nomadic Mongol hordes. But then that legend needs some serious re-evaluating (see box, below).

Credit: Annabel Ross Jones

The long drive back to Hoyor Zagal required a shortcut. Outside Khushuu Tsaidam, a monument to a seventh century AD Turkic leader, we turned off the paved road and took a 28-kilometre off-road adventure via the town of Khashaat. Out here in the infinity of grassy plains you really are a speck in time and space. I thought of an early 1970s record sleeve artwork by the great American designer Saul Bass. It shows a tiny figure traversing a vast green and tawny landscape. Perhaps he’d taken the same lonely road to Khashaat. The title of the record was Freedom is Frightening, by Japanese percussionist Stomu Yamashta.

Freedom in post-Soviet Communism Ulaanbaatar hasn’t been so much frightening as confusing. The skyline is a contradiction of pagodas and glossy skyscrapers, Soviet-era leftovers and garish restaurants purveying every kind of Asian food.

Prosperity has been a fragile plant for many Mongolians, but there’s tangible, solid growth in the shape of the capital’s best hotel (the Shangri-La) and industries (including cashmere). The Shangri-La, a commanding wedge just south of Chinggis Square, has, in two years, become a destination in its own right for locals and visitors, with its pumped-up health club, shopping mall, a top floor swimming pool straight out of a design magazine and a club lounge surveying the city – past, present and future – and its encircling mountains.

Mongolian cashmere, the finest in the world – whether from the top quality Gobi or the more fashion-oriented Goyo labels – is the product that attracts most visitors. I succumbed to a featherlight, super-soft Goyo overcoat costing the same as an average wool blend garment in a London or Hong Kong shop, and worth thousands of dollars in the high-end versions. The state department store is worth a browse for its oddity alone, while nearby fairtrade shop Mary & Martha has an excellent selection of shawls, stationery and blankets.

You’ll probably have a bulging suitcase and photo gallery on the way home. But it’s a decluttered brain that’s the real souvenir.

The Mongol empire: bloodthirsty barbarians or talented bureaucrats?

It gives you a slightly queasy feeling landing at an airport named after Genghis Khan, a byword for bloody slaughter and barbarianism.

But the Mongolians have every reason to be proud of their historic empire if recent academic research is to be believed.

In The Silk Roads, author Peter Frankopan writes that the ruthlessness of the Mongols’ conquests obscures the tolerance and skill that marked the way they subsequently ran those vanquished cities. As you see at Karakorum, religious diversity was encouraged. Their administrators kept taxes low and prices keen, ‘symptomatic’, he writes, ‘of [the empire’s] bureaucratic nous, which gets too easily lost beneath the images of violence and wanton destruction…their success lay not in indiscriminate brutality but in their willingness to compromise and cooperate’.

Need to know

Shangri-La Hotel, Ulaanbaatar shangri-la.com/ulaanbaatar

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan, China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)