As the great monolith of Uluru lies in the dry heart of the driest continent on Earth, let’s start with some dry facts about it.

Uluru, located in the Australian Northen Territory’s Uluru Kata-Tjuta National Park, is a desert formation made of the sedimentary rock arkose. It is 863 metres high with a circumference of 9.3 kilometres. It’s also a very strange natural phenomenon called an inselberg. They are so named because, like their cousins in the Arctic and Antarctic oceans, the vast part of these marooned, inland mountains lies below the surface. You would need to drill six kilometres down before you reached the bottom of Uluru.

Maybe they’re not such dry facts after all. Like so many things about Uluru, even the physical science is mind-boggling and mysterious.

Our first encounter is at dawn.

The light from a full moon is still high in the western sky. It blends with the first sunlight of the day. The desert scrub gradually fills in with shades of tawny, dark green and the deep brick-red of the soil.

And there it is, this huge, solid, yet weirdly ethereal presence. As the light catches it, there are dark folds on its flank like a great curtain on the horizon.

We grab a coffee and something to eat, and begin the base walk. It’s 8.30am on a Northern Territory winter morning. It’s also something of a new dawn for Uluru, for the people from all over the world who work here – and for the Anangu, the people who own the land.

In October 2019, a prohibition on climbing Uluru came into force. An Australian prime minister had agreed to the ban 36 years before. In between, there were battles and backsliding, as commercial, religious and ideological interests clashed.

But the day finally came. That was the end of one Uluru story, the one that began when an explorer called William Gosse ‘discovered’ the monolith and, in the sycophantic or (maybe) calculating way of 19th-century explorers, named it after a premier of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers.

In giving back Ayers Rock, or Uluru as it was again known, to the Anangu, Australia also gave the site back its isolation and its mystery.

Credit: Getty Images

The campsite under the rock was removed. From then on, visitors would stay outside the boundaries of the national park.

That campsite had been made famous, or notorious, by the Lindy Chamberlain case, where a dingo was eventually proved to have taken the child of a camping visitor. That case became a Hollywood film, bringing more visitors and an even greater sense of sorrow to the Anangu. Despite the chain link fence drilled into the windy ridge, climbers fell to their deaths: 37 of them in all, before the ban on climbing came in.

I was there shortly before the ban came into force. There were still a few people scaling the rock. From below, it looked like an unbearable act of intrusion, like watching base jumpers on the Taj Mahal or abseilers on Canterbury Cathedral.

So, justice was done and Uluru was restored. Henceforth, only strictly controlled guided tours , like the one I am on this morning, would visit the rock. You are discouraged from even touching it, except in a couple of sanctioned areas. You are even told not to photograph certain aspects of the rock, where ancient tributes to the departed are marked.

For very good reasons, Uluru became the land of don’ts, a place of prohibition. How to find a new, positive story to attract a new generation of visitors?

The answer was as bold as it was fitting. Uluru would tell the Anangu story, their oldest story of all, how it and the Earth itself came to be. And it would do it in the ancient songs and poetry combined with the most up-to-date light and sound technology around. Wintjiri Wiru, as the show is called, joins Bruce Munro’s Field of Light installation which sprawls across the desert sands.

I’d heard that a big name in concerts and shows was involved. That media architect, as he’s known, is Bruce Ramus, who has designed spectacular events for bands like U2 and Queen, as well as the Grammys and Oscars shows. Now he was being asked to help the Anangu people tell their origin myth in the skies.

“We undertook years of technical, environmental and cultural research,” Ramus tells me. “And that enabled us to develop the designs that became the show.”

In fact, it would take six years of working in the searing heat and coping with the clouds of ravenous Australian flies which plague the region in summer. But more than that, it took patience and a lot of listening as a council of Anangu elders worked with the team to make the story come to life.

And here I am, at dusk, about to see it.

There’s that full moon again, a ghostly pink now, rising just above the horizon. To the west, the sun sinks in an orange sea punctuated with dark clouds. Between the two, Uluru lies, darkening; an elemental scene that has played out since the beginning of time.

For the Anangu, the real story of the beginning of time is about to be told in the skies as the canvas morphs from deep blue to rosy charcoal.

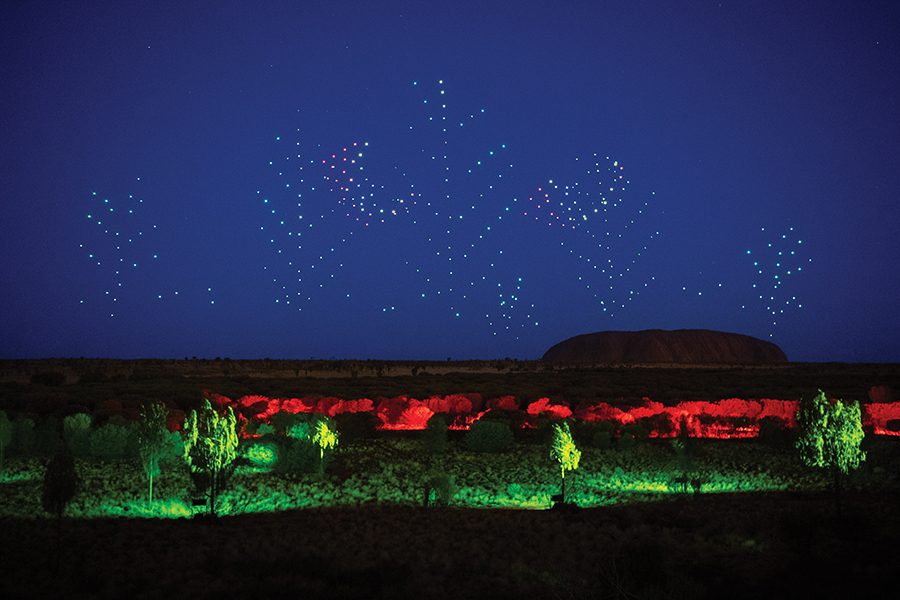

This is the story of the Mala people, named after the mala, or rufous hare-wallaby, which used to inhabit these parts. Suddenly, the carpet of desert oaks stretching towards Uluru (a dim, dark curve now) comes alive. Flickering, fire-like light picks out the trees as the mala creeps from bush to bush.

Credit: Felix Cesare / Getty Images

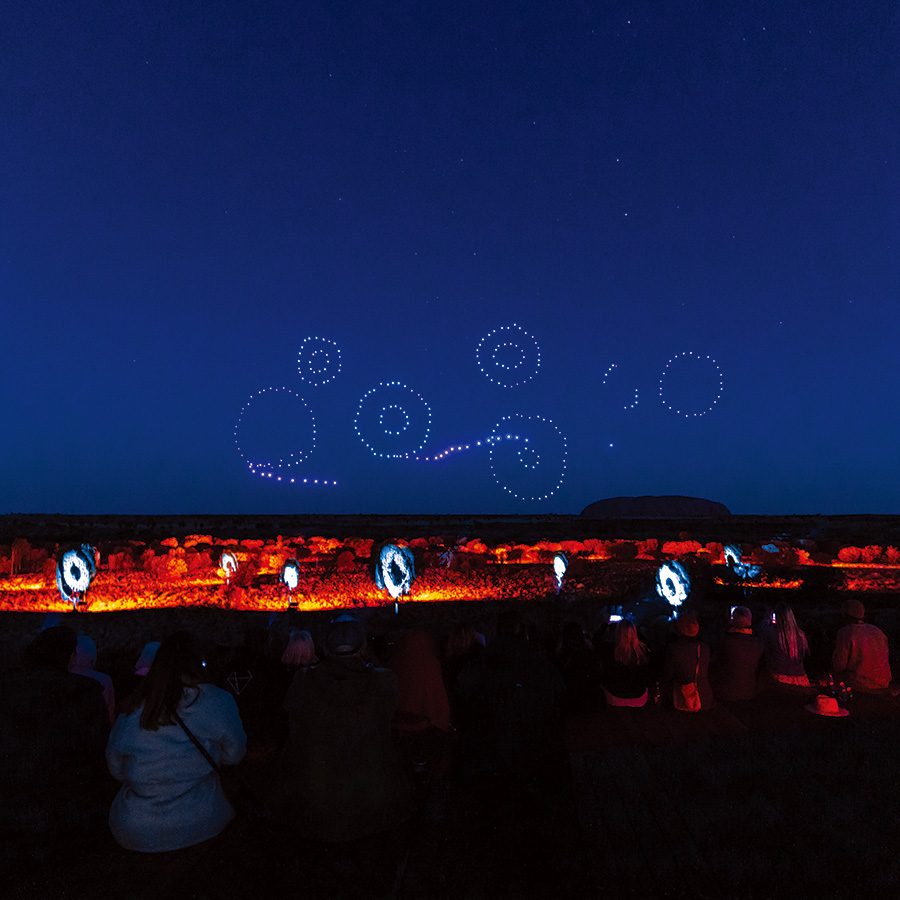

Those images, projected by invisible lasers, become still. Then, a thousand drones take to the skies, like a squadron of stars. They form and reform, as songline circles bridged by waves, as trees as tall as skyscrapers and as birds that fill half the sky. Finally, red and white pinpricks into the face of a giant devil dog.

In the Mala myth, the dog is one manifestation of an evil spirit conjured up by a hostile tribe. The kingfisher woman warns her menfolk, but they flee too late: only the women escape.

The drones return gently to earth and the laser lights lap gently like an inland sea at our feet. And that’s it: 20 minutes of the world’s biggest permanent light show, and an experience no one here, either sitting alongside me in the amphitheatre with our wine glasses and food hampers by our side, or congregating on the viewing platform a few metres behind us, will ever forget.

Thinking about it later, I saw that memory – or maybe not forgetting – is at the heart of Wintjiri Wiru, not the requirements of a global tourist destination to find a new story.

One of the singers whose voice is heard as the drama plays out in the skies is the artist and teacher Awalari Esther Teamay. She sees the project as a way of building bridges with younger generations and with the wider world.

“This is great for Anangu,” she says. “It will create job opportunities for our young people to work and share our stories.”

But there’s something deeper, too. “This is about teaching our younger people, the next generation to take over and teach our stories.”

Credit: Eliud Kwan

How to get there

Ayers Rock/Connellan Airport is served by flights from Sydney, Cairns and Brisbane. Uluru is 465km from Alice Springs by road.

Credit: Eliud Kwan

Where to stay

Ayers Rock Resort comprises seven hotels and camps. These include the luxury Longitude 131 camp and Sails in the Desert hotel, where rooms start at A$475 (HK$2,500) to the Ayers Rock Campground, which has pitches from A$43 (HK$230) per night.

More inspiration

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)