Walking along Dixon Street in Sydney’s Chinatown during its Friday Night Market is like stepping into a colourful, crowded, kitsch-filled Asian kitchen: how many flavours, languages, scents, sounds and cultures can we throw together to feed one massive family and guests from all over?

Multiple generations of different ethnicities flock here for a seat at one of its 200 or so restaurants at all hours. But like so many other Chinatowns in the world, the roots of its inception were far less wholesome.

‘It used to be called Sleazetown,’ octogenarian local expert George Wing Kee informs me.

‘It was a ghetto before World War Two. Australian people didn’t come here to eat.’

Credit: Irwin Wong

The area is close to the wharves and became a place for enterprising seamen to stealthily unload contraband such as opium. There was also the (quite true) impression that up to 100 undocumented Chinese migrants lived in cramped quarters above each storefront. Considering that the White Australia policy restricting the migration of non-Caucasians into the country was only dismantled in 1972, being Chinese and ‘illegal’ pretty much went hand in hand in those days. During World War Two, many of these migrants were employed as cheap labour by merchant ships sailing between Europe, the US and Australia, and, realising they would be out of work when the war ended, jumped ship wherever they could. Those in Sydney inevitably joined the expanding Chinese nucleus that would come to be known as Chinatown.

By the time my family arrived in 1983, Chinatown was on track to becoming a tourist destination as part of Sydney’s new multicultural outlook. Up went the traditional symbols that still stand today: Tang-dynasty style ceremonial arches inviting fortune and luck; a pagoda; a refurbished Dixon Street reminiscent of Chinese alley culture with restaurants, shops and grocery stores.

Credit: Irwin Wong

For my parents, it was a place that unambiguously reflected back their culture as well as fulfilling other, more urgent needs. At that time, the only Asian supermarkets were in Chinatown. My mother was our sole breadwinner yet would also take a 45-minute bus ride several times a week to buy the groceries she needed to feed her children, husband and in-laws who longed for the flavours of their homeland.

‘Australia was boring in the ‘80s,’ my mother tells me over the phone. ‘Shops were closed after 5pm every day of the week. There was nothing to do, nowhere to go – except Chinatown.’ She pauses. ‘And Kings Cross.’

Credit: Irwin Wong

As a child, it isn’t very different weaving between restaurant hawkers in Chinatown and nightclub spruikers in Kings Cross, Sydney’s red light district. But as an adult I can see other similarities between the two places: both Chinatown and Kings Cross are regarded as outliers in the idealised Sydney landscape. Both exert an exotic allure, and a mix of comfort and chaos. And both at one time offered my family what they needed to feel less displaced: the physical immediacy of life in all its vivid and varied forms.

But today, while Kings Cross’ bohemian reputation has languished, Chinatown has moved from the fringes to the mainstream. Sydney’s Chinese New Year celebrations are the largest outside China, with more than a million visitors celebrating last year. After its 20th-century White Australia policy, the country is now all about embracing the Asian century.

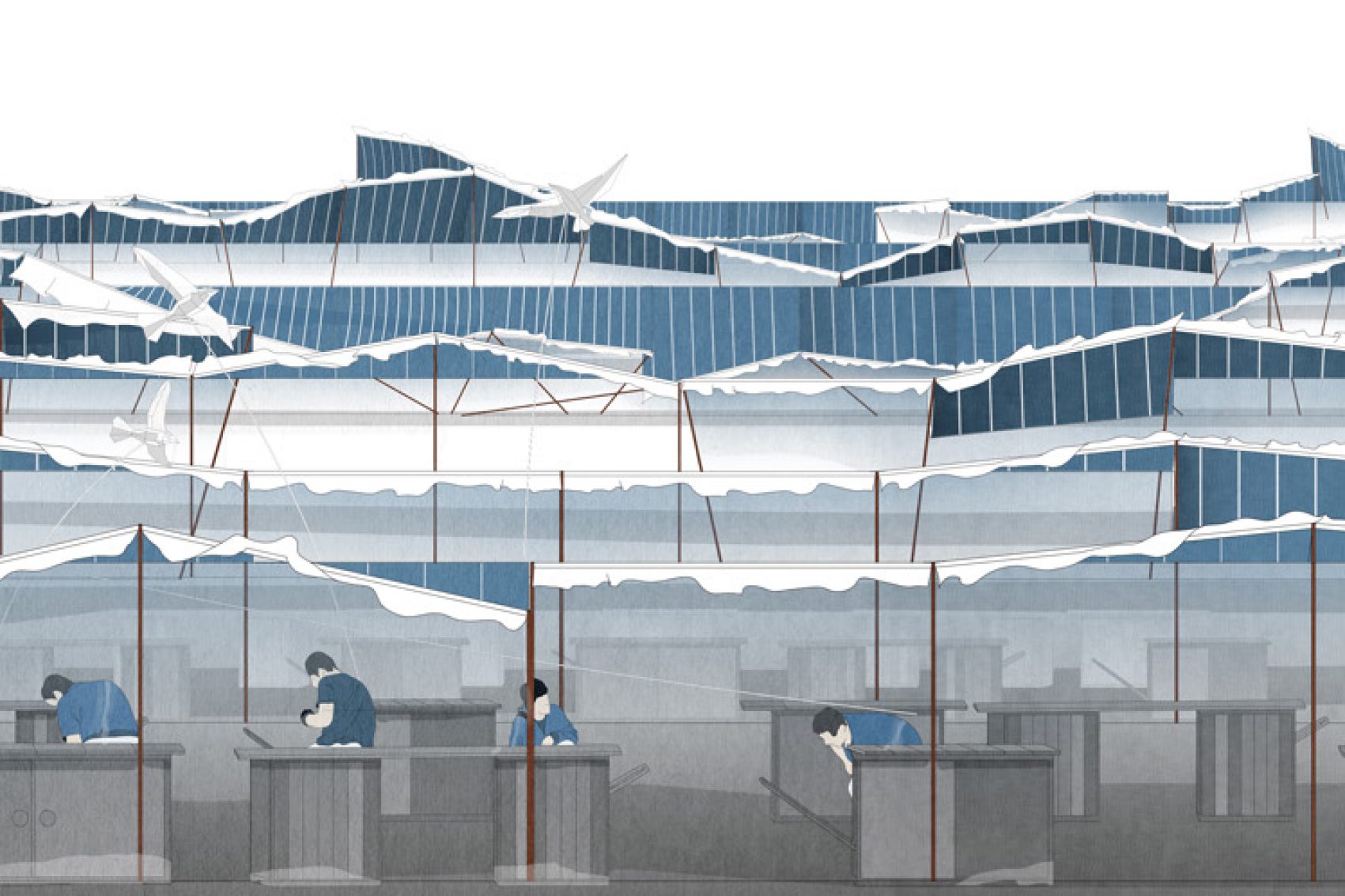

The public art in the area expresses this growing consciousness. A mural of Aboriginal rights activist Jenny Munro watches over Harbour Street and Goulburn Street. The Golden Water Mouth – a yellow box gum tree covered in gold leaf – serves as a symbolic entry point on the corner of Hay and Sussex. Lindy Lee’s New Century Garden borrows elements from the design of a traditional Chinese Garden to create a public domain for rest and reflection. Jason Wing’s In Between Two Worlds consists of 30 suspended blue spirit figures inspired by his Aboriginal and Chinese heritage.

Credit: Irwin Wong

‘China is more than a singular entity,’ says Mikala Tai, Director of 4a Centre for Contemporary Asian Art , which has fostered Chinatown’s art projects with the City of Sydney over two decades. ‘I think it’s important to be breaking the idea of a monoculture by showcasing more complex layers of identity.’

Meanwhile, Chinatown is a neighbourhood in flux, and its preservation is at the mercy of development plans. But perhaps its uncertain future isn’t a reason to grieve. After all, its original raison d’etre was as an enclave for working-class, alienated Chinese immigrants to eke out a better life. So it’s not all bad that the need for Chinatown has diminished.

Credit: Irwin Wong

And Chinatown will continue to be a cultural heartland for those who relied on it as a familiar place in a strange land. As I study the grainy photos of my grandparents in front of the Dixon Street stone lions, I am hopeful that this will always be a place of sanctuary and reinvention.

Jenevieve Chang is author of the memoir The Good Girl of Chinatown

This story was originally published in February 2018 and updated in September 2020

Credit: Sam Ki

More inspiration

Sydney travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)