What is South African food?

Travel magazines have long waxed lyrical about Cape Town’s craggy mountains, white sandy beaches, colourful architecture and brilliant sunshine, while entire books have been devoted to the beauty of nearby Franschhoek and Stellenbosch and the superb wine produced in their Cape Dutch farms. But the food? Well, let’s just say that the meat-focused meals and overly sweetened vegetables weren’t anything to write home about.

The problem with being from one of the most culturally diverse nations on earth is that it is rather difficult to choose which tradition to celebrate. And for years, South Africa, a country of 11 official languages, had no idea what its national cuisine was. Apartheid must shoulder a lot of the blame for this. Up until 1994, South Africa operated under minority rule, which meant that any non-white tradition was deemed irrelevant. So the rich world of Cape Malay, Indian, Zulu, Xhosa and Khoisan cooking was swept aside in mainstream restaurants for a focus on European fine dining and classic Afrikaans recipes.

And to make matters worse, as members of a pariah nation, South Africans were unable to draw on the necessary inspiration from international culinary trends. Banned from travelling to a number of Western cities and based in a country that was firmly off any sort of tourist trail, local chefs had no way of expanding their knowledge.

Credit: Claire Gunn

‘Apartheid meant that none of us could go abroad or even explore our own heritage, so we were all stuck here cooking the same things over and over because of some idiots who made terrible decisions,’ says Chris Erasmus, the head chef at the award-winning Franschhoek-based Foliage Restaurant. ‘I grew up in Malmesbury [a small town in the Western Cape] and during my younger years as a chef I felt trapped, like I was missing out on the reality of my own country and the rest of the world.’

Today, Foliage is one of the most critically acclaimed restaurants in the Western Cape and a wonderful illustration of exactly how far South Africa has come in the past 23 years. Diners can look into the open kitchen, which is staffed by chefs who are Xhosa, Zulu, Afrikaans, Coloured – denoting a distinct South African racial group made up of numerous ethnic backgrounds – and English, all of whom incorporate family recipes into the seasonal menu.

‘We get milk fermenting techniques from our Xhosa colleagues and bean-stew recipes from our Zulu ones and Cape Malay dishes from our Coloured friends – and our food is the better for it,’ says Erasmus. ‘But we’re not alone. The restaurant scene here in Cape Town is getting really diverse as chefs are finally starting to find an identity separate from Europe and our colonial past. Fifteen years ago, South African restaurants were all the same, but not any more.’

Erasmus himself has been studying the culinary traditions and the foraging techniques of the Khoisan people, a group made up of San hunter-gatherers and the Khoikhoi of the Northern Cape. Famous for creating some of the most compelling rock art in the world, their culture and traditions have survived in the desert lands near the Namibian border and are now being recreated in Cape Town restaurants in dishes such as saltbush lamb stew and honey mead pudding.

But interestingly, the country Erasmus draws the closest parallels to is China. ‘Cape Town was a key stop on the Spice Route, and heavily spiced recipes have been a part of community cooking for centuries,’ he says. ‘Like China, both our countries were ignored by the rest of the world for a long time, which meant they became quite inward-looking. They also both have a strong focus on preserving food and use lots of salt and sugars, playing off the idea of sweet and sour flavours.’

Credit: Claire Gunn

Credit: Claire Gunn

The Spice Route has played an integral part in making South African cuisine what it is today, not least because during the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch East India Company imported thousands of Javanese and South Indian slaves to work on Cape farms. Today their descendants speak Afrikaans and have fully integrated into the Cape Town Coloured community but their strong culinary traditions live on.

And any visitor to Cape Town should visit the beautiful jewel-like houses of Bo-Kaap – and not just to get an Instagram-worthy picture, but for the authentic Malay restaurants such a Biesmiellah and Bo-Kaap Kombuis, which serve biryani, bobotie, samosas and chilli bites under the shadow of Lion’s Head mountain.

‘It is an incredibly special place,’ says chef Reuben Riffel, who runs hugely popular restaurants of his own in Paternoster, the Waterfront and Franschhoek. ‘I come from a small Coloured town and community is so important to us. Naturally things change, but in Bo-Kaap it has stayed the same. While Apartheid laws destroyed so many communities across South Africa, the forced relocations encouraged those who stayed to deepen their traditions, and food became an especially powerful reminder of who we were.’

Credit: Claire Gunn

And as Western food critics finally turn their long overdue attention to Africa, a number of these restaurants are winning international acclaim. Luke Dale-Roberts is head chef of The Test Kitchen, which has appeared annually on the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list since 2014, and he is a firm believer that South Africa is set to become a culinary destination to rival Japan and Italy within the next decade.

‘We have everything here: incredible produce, the space and the landscape to create beautiful restaurants, talented chefs and a diverse, unique range of gastronomic traditions,’ he says. ‘And slowly we’re getting the confidence to stop copying Europe and instead start celebrating just how unique we are.’

Credit: Mark Williams

Where to stay

Babylonstoren is a Cape Dutch wine and fruit farm that has been transformed into one of the loveliest places in Cape Town to spend the day or night. The grounds are an attraction in their own right, filled with plum trees, hydrangeas and cacti.

The Mount Nelson is a Cape Town institution and a pretty-in-pink tribute to a past era, featuring wooden floors, ceiling fans and a long veranda to have afternoon tea on.

What to eat

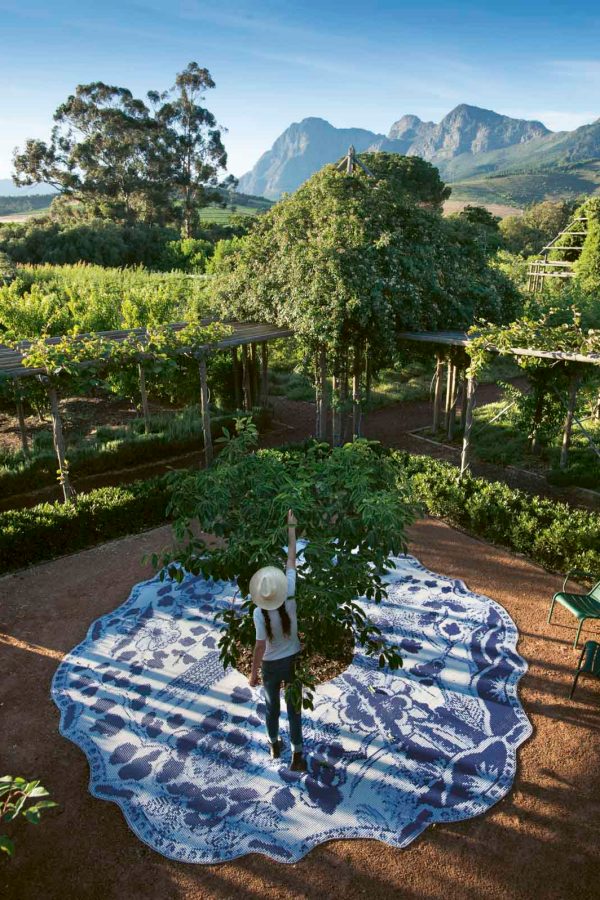

The Franschhoek Valley is famously photogenic, and Boschendal , with its 17th-century main house, shady oak trees, lakes and generous outdoor picnics on the lawns, is the prettiest of the local wine farms.

Sitting on the sixth floor of a silo building, the Pot Luck Club focuses on small plates like beef fillet with chocolate and coffee sauce, or a nectarine almond tart served with malted-popcorn ice cream.

Credit: Suretha Rous / Alamy Stock Photo / Argus photo

Credit: M.Sobreira / Alamy Stock Photo / Argus photo

What to do

Walk all the way from the top of Bree Street, which starts under Table Mountain, down to the bottom, which ends near the Waterfront, and pop into the furniture shops, fashion boutiques and coffee bars. You’ll also find acclaimed tapas restaurants, crayfish bars and Israeli food.

Local gin & tonic

Head to the Gin Bar, located in a beautiful courtyard scattered with roses, or Mother’s Ruin, both focusing on South African-made gin, which is flavoured with fynbos, a fine-leafed shrub indigenous to the Cape.

More inspiration

Johannesburg travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)