The greatest walls of China

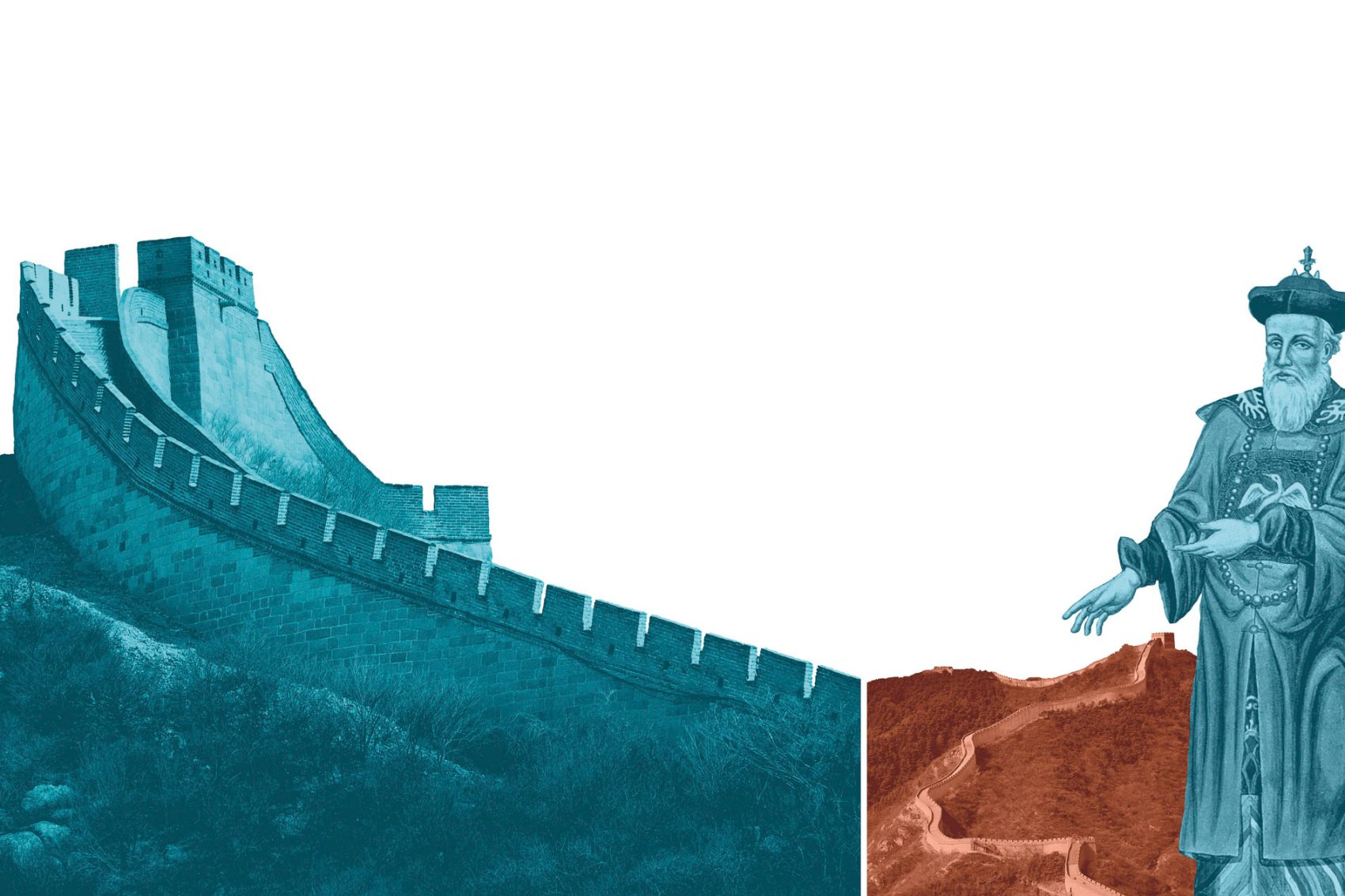

The broad grey ramparts and turreted watchtowers of The Great Wall rising over green mountains create an unforgettable symbol of power, and of China’s long and illustrious history.

Ferdinand Verbiest, a 17th century Jesuit scholar employed by the Manchu Qing government, declared that ‘the seven wonders of the world put together are not comparable to this work’. In 1935, Mao Zedong wrote, ‘No man is a hero unless he’s been to The Great Wall.’ In 1778, Samuel Johnson said that visiting The Great Wall would benefit future generations: ‘There would be a lustre reflected upon them from your spirit and curiosity. They would be at all times regarded as the children of a man who had gone to visit the wall of China.’

The Great Wall is a misnomer. It is not one, but many, many walls, built from the seventh century BC to the 16th century, and stretching, often doubling up, between the semi-desert of Gansu province in China’s northwest and the steep cliffs of eastern Shandong province, where a rampart tumbles down into the sea. Estimates of the length of this massive collection of walls range from 6,350 kilometres to 21,196 kilometres (a recent figure made possible by modern archaeological technology).

The brick walls of Hebei and Shandong provinces are very different from the yellow-earth walls in Gansu, and to some extent they served different purposes. Some of the earliest walls, built for defence as separate states evolved in the north of China from the seventh century BC, were linked and improved by China’s first emperor in the third century BC, when he overcame all the other warring states and created a unified China.

But it was during the subsequent Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) that the wall was extended, along the Silk Road into Gansu, reflecting the westward expansion of Han China into Central Asia. At the end of the Han dynasty, wall building stopped for more than 1,000 years as the Chinese state perceived little danger from invasion. The next great period of wall building was during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) when various northern groups such as the Mongols and the Manchus presented a serious military threat.

Here are four different walls in four very different places that each tell us something about the history of China.

The iconic wall

Badaling

Easily reached from Beijing, the wall at Badaling is well restored. It’s the site most toured by visiting royalty and presidents. Take in the Cloud Platform, a tower built in 1345 that straddles the road, at nearby Juyongguan. Inside the tunnel-like passage, low-relief Buddhist figures and inscriptions in Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian, Sanskrit, Uighur and Xixia reveal the complex meeting of cultures in northern China during the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1279-1368).

The wall at Badaling is a broad structure along which five horsemen could ride abreast, running up to watchtowers, the steepest parts ascended by steps. The wall here was reinforced with bricks during the 16th century when the Ming dynasty was faced with serious threats from the Mongols and the Jurchen in Manchuria. Defensive garrisons were housed in a series of forts, watchtowers and beacons, on which fires were lit to send smoke signals – all to protect the capital, Beijing. It also served as the model for The Great Wall in Zhang Yimou’s recent film of the same name that features a broad, brick wall complete with watchtowers: although during the Song dynasty (960-1279), in which the film is set, the wall would have been in disrepair and constructed of stones and earth.

The vertigo-inducing wall

Simatai, Jinshanling, Gubeikou, Mutianyu

Interesting sections of The Great Wall near Beijing that have been opened in recent decades include Simatai, Jinshanling and Gubeikou. They form part of the wall that was extensively restored in the 16th century, and though they generally run narrower than the Badaling sections, the mountain scenery is more dramatic.

Simatai’s 5.4 kilometres of wall, including 35 beacon towers, clings to the Yanshan Mountains and is incredibly steep in parts (though there are open-air gondolas for the faint-hearted). Jinshanling, west of Simatai, is a 10.5 kilometre stretch with 67 watchtowers and three beacon towers (and a cable car). Both sites are linked to the dilapidated 40 kilometre section at Gubeikou.

All came under the control of a famous 16th century general, Qi Jiguang, who masterminded the restoration between 1567 and 1570. He undertook the work late in life, after a long period of service defending China’s southern coast against Japanese pirates (his wife was also said to have commanded a coastal fort). It was the Gubeikou section that Lord Macartney visited on the first British diplomatic mission to China in 1793. His valet, Aeneas Anderson, wrote: ‘This wall is, perhaps, the most stupendous ever produced by man…the idea of the grandeur, and the active labour employed in constructing it is not easily grasped by the strongest imagination…In short, it formed a fine military way, by which the armies of China…could march from one end of the kingdom to the other.’

The poignant wall

Shanhaiguan

Near the easterly city of Qinhuangdao in Hebei province is the Shanhaiguan section of The Great Wall – so far east that the wall reaches the sea, descending into the waves at a portion named Laolongtou (Old Dragon Head).

It’s also significant for being the section that demonstrated the fact that the wall was no guaranteed defence when, in 1644, the Ming commander Wu Sangui opened the gates to the invading Manchu army. His loyalties were complex: his family came from an area close to the Manchu heartlands and his uncles had joined the Manchu; but Wu remained a loyal military commander of the Ming forces. However, when the last Ming emperor died and Wu’s father was brutally murdered by the rebel leader briefly occupying Beijing, he changed sides and the Manchu army poured through wall to take Beijing.

Nearby Shanhaiguan is Mengjiangnu Temple, which commemorates one of the most poignant legends associated with the wall, Meng Jiang.

According to the legend, Meng’s husband was conscripted when the first emperor ordered work on existing walls in the north, joining them to form a long defence, during the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC). At the time, a man’s tax responsibility included periods of service in government infrastructure projects. Her husband was sent off to the far north, and, come the winter, she decided to take him warm clothes. Near Shanhaiguan, she learned that he had died. She sat by the wall and wept, and her tears caused the wall to crumble and reveal his body, which she took home for burial.

The humble wall

Yumenguan, Jiayuguan

Out in the Gansu corridor, a semi-desert route between mountain ranges on the old Silk Road, you can see traces of a very different wall: most notably at Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass) near Dunhuang. Built 2,000 years ago during the Han dynasty, the wall is made of tamped earth. You can still see the layers of yellow earth pounded flat within a wooden framework, sometimes strengthened with layers of tamarisk twigs or bundles of reeds, scoured like ribs by wind and sand.

Here, the wall is simply a wall, a marker rather than a defensive structure, but part of a system of widely spaced garrisons where the Han army kept watch on its westernmost borders. Alongside the wall are beacon towers, built from the same layers of pounded yellow earth. Fires were lit on top of the beacons to signal alarm to other garrison troops using smoke signals. The block-like structure at Yumenguan towers over the smaller beacons.

Also in western Gansu province is the great fort at Jiayuguan, the best-preserved fort of the Ming-era walls. Built of mud brick and tamped earth in the late 14th century and recently restored, it is a dramatic sight with its massive yellow walls and elaborate corner towers standing tall in the desert.

5 other Great Walls of China

You know the big one – but many other ancient fortifications survive across the Middle Kingdom. We introduce the most historic, grand and formidable.

Credit: Quanjing

City wall of Xi’an

Built: 14th century, refurbished three times

Purpose: to protect Xi’an, the capital city of Shaanxi province

Claim to fame: most complete city wall in China

Interesting feature: a many-windowed tower designed for shooting arrows at attackers

Constructed during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to protect against invaders, this structure now separates modern Xi’an from the ancient city centre. It stretches 14 kilometres and reaches 12 metres high, standing as one of the world’s largest ancient military defence systems and the most complete, connected Chinese city wall. Despite surviving for hundreds of years, the structure faced a different kind of threat in the 1950s, when there was an attempt to demolish it. Thankfully that didn’t happen, and China has officially declared the heavily restored wall a heritage site. Apart from its historical significance, tourists and locals alike are drawn to its recreational use today: the top of the wall is a cycling loop, which takes about 90 minutes to finish.

Credit: David South / Alamy Stock Photo / Argusphoto

Miaojiang Southern Wall

Built: 1573 to 1622

Purpose: to separate the Miao and Han ethnic groups

Claim to fame: the only Great Wall in southern China

Interesting feature: lush forested surroundings

Historically, many large-scale walls were built to create boundaries between various warring groups. During the Ming dynasty, the Miao people staged several uprisings in response to imperial assimilation efforts. This 190-kilometre wall was built because of these attacks, in modern-day Xiangxi Autonomous Prefecture in Hunan, with more than 1,300 sentry posts for guards.

It’s not the strongest wall – the stones used are relatively small – as the Miao people did not have a powerful military, but it is considered a part of the Great Wall of China network based in the north. Today only small parts of the Southern Wall remain intact, but they offer great hiking along the lush mountainside. The nearest village, Fenghuang, is known as one of the most beautiful towns in China, with green slopes and a river running through it.

Credit: Imaginechina

Hill wall of Gongyi

Built: starting 1861 or earlier

Purpose: to protect a military outpost

Claim to fame: most recently discovered wall

Interesting feature: steep mountain location

It’s incredible, in this day and age, that a 1,000-metre wall could go undiscovered. Yet it was only in 2015 that this fortress, tucked high in the mountains of Henan province’s Gongyi, was found. With very few documents acknowledging its presence, historians have had to rely on studying its structure to learn about its past. The 1,000-metre wall encircles a mountaintop, suggesting it was built to surround a fortress rather than as a boundary between warring groups. It is in relatively good condition, with three of its four walls mostly intact, thanks to its hidden location in a remote area of central China, where it’s surrounded by steep cliffs and rocky natural terrain that deter explorers.

Credit: Quanjing

Nanjing City Wall

Built: 1366-1393

Purpose: to protect Nanjing, the capital of the Ming dynasty

Claim to fame: the world’s longest city wall

Interesting feature: brickwork joints were poured with a mix of lime mortar, water in which glutinous rice had been cooked and tung oil

With 25 of its original 35 kilometres still intact, the Nanjing City Wall is the world’s longest city wall. The founder of the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang (1368-1398), ordered up to 350 million bricks from the 118 counties in his empire to build it. According to his specifications, each brick was inscribed by the individual official or artisan who was responsible for its size and quality, leaving lasting legacies of ancient Chinese calligraphy. A highlight is Zhonghua Gate, one of the most intricate and well-preserved defensive gateways in the world.

Credit: Ray Wise / Moment Open / Getty Images

Wall of Pingyao

Built: starting in 1370

Purpose: to protect the city of Pingyao

Claim to fame: surrounds the best ancient city in China

Interesting feature: Pingyao is called Tortoise City because the city wall resembles a tortoise from above

Pingyao is famous for being the birthplace of modern banking and for its magnificent ancient wall. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the ancient city and its wall represent the evolution of Chinese architectural style over a span of five centuries. A wall made of rammed earth was built in 827 BC, but the brick version we see today was constructed during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1912), when the city served as a financial hub. Archaeologists are fascinated by the city wall; according to local lore, its 72 watchtowers and 3,000 external battlements represent the 72 disciples and 3,000 students of Confucius. Amid Pingyao’s rows of pretty streets, highlights for visitors include the ancient Ming-Qing Street, the city’s busiest commercial block for hundreds of years, and the Temple of Confucius, which remains the best-preserved Confucius temple in China.

Hero image: David South / Alamy Stock Photo / Argusphoto

Beijing travel information

- China – the Chinese Mainland, Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR and Taiwan Region

- Hong Kong SAR - English

- Chinese Mainland (China) - English

- Taiwan China - English

- 香港特別行政區 - 繁體中文

- 中国內地 - 简体中文

- 中國台灣 - 繁體中文

- Africa

- South Africa - English

- Asia

- Bangladesh - English

- Korea - English

- Singapore - English

- Cambodia - English

- 한국 - 한국어

- Sri Lanka - English

- India - English

- Malaysia - English

- Thailand - English

- Indonesia - English

- Maldives - English

- ประเทศไทย - ภาษาไทย

- Indonesia - Bahasa Indonesia

- Myanmar - English

- Vietnam - English

- Japan - English

- Nepal - English

- Việt Nam - tiếng Việt

- 日本 - 日本語

- Philippines - English

- Australasia

- Australia - English

- New Zealand - English

.renditionimage.450.450.jpg)