One of the biggest challenges resulting from COVID-19 has been how to handle the sudden large number of idle aircraft caused by the decreased demand for travel. With 70 per cent of our passenger fleet grounded at the height of the pandemic, we had to find a way to store our aircraft, keeping them safe and protected when they weren’t flying.

Our teams in Hong Kong and Australia worked hard to devise a solution, developing a parking operation of unprecedented scale and complexity.

First, the team needed to find a suitable location that had both the space to accommodate large numbers of aircraft, and the right environmental conditions to keep them protected. The answer? Alice Springs, in the middle of the Australian desert.

“The biggest enemy of a parked aircraft is corrosion from sitting on the ground for long periods in humid conditions – especially when located in a coastal environment where that humidity has a salt content,” explains Benjamin Connell, Regional Engineering Manager Southwest Pacific. “That’s why we chose Alice Springs. It’s in the desert where it’s inland, very dry, with a low humidity of around 20 per cent, and no extreme weather events like tropical cyclones.”

But while a desert might be optimal for aircraft storage, it presents a unique set of challenges for teams on the ground.

“One of the issues with being based in Alice Springs is that by about 8am the surfaces of the aircraft are too hot to touch - we could literally fry an egg on them – so the team have to plan their maintenance schedules quite differently,” says Ben.

The desert terrain is also a challenge. Unlike the firm foundations of an aircraft hangar and the surrounding aircraft stands and taxiways, at Alice Springs aircraft are parked on compacted strips of soil and concrete that are mixed to form a hard surface. Performing maintenance around these limited sized parking strips can be challenging whilst moving aircraft also requires complex and special towing procedures.

“And we’ve had no shortage of interesting wildlife,” adds Ben. “I was talking to an engineer one day when a giant goanna [lizard] walked out of the grass, straight past us and between the landing gear!”

Environmental factors aside, the unprecedented scale of the aircraft storage operation was a huge challenge to manage in itself.

“Parking aircraft at Alice Springs is not something many of the team have done before, and certainly not on this scale, so in many ways it was exploring uncharted territory,” explains Pearl Sau, Line Maintenance Operations Manager.

As Alice Springs isn’t a commercial airport, the teams had to liaise with numerous authorities to procure special authorisation and flight permissions in order to fly the aircraft to Alice Springs.

“Another huge challenge was shipping the necessary spare parts, tools and equipment required in Alice Springs,” says Pearl. “With all the travel restrictions in place, and the very low frequency of flights between Hong Kong and Australia, it was incredibly difficult for us to arrange the shipping logistics.”

Once everything was in place, the work could begin.

“What many people would not appreciate is that the maintenance required for a parked aircraft is just as much as for an aircraft that is flying,” explains Pearl.

“Safety and maintaining compliance with manufacturer and regulatory airworthiness requirements is our number one priority, whether the aircraft is flying or not – and we have to ensure the aircraft are maintained in a condition where they are able to be reactivated to re-enter operational service when required.”

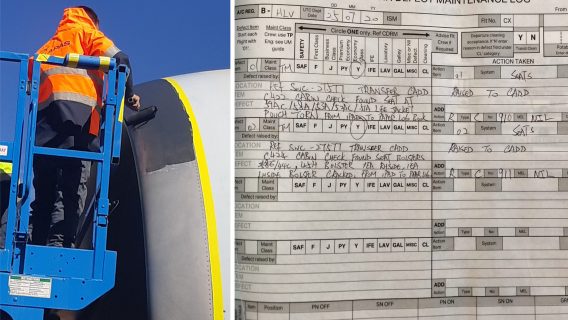

The first phase of parking an aircraft is called the induction, which takes around 14 days per aircraft. This involves covering windows, external surfaces, instruments, sensors and any openings. The team also have to secure the engines, replace the engine oil with inhibiting fluid to prevent corrosion, introduce additives to fuel tanks to prevent microbial growth, and a myriad of other tasks.

After phase one, the teams move to a periodic check arrangement, with specific maintenance checks to carry out at regular intervals after seven days, 14 days, 30 days, and so on, up to a one-year check.

The final phase is reactivation, which takes approximately four to six months of planning, plus four weeks of solid work by the engineers. But again, the process isn’t straightforward.

“Every reactivation is different and presents different challenges,” explains Ben. “The team first has to reverse everything they did during the induction process: removing the inhibiting oils, adding fresh oil, removing protective covers and so on. We address any maintenance issues we find and then it’s on to detailed testing of engines, systems and components to ensure the aircraft are fully airworthy for the flight out of Alice Springs.

Thanks to travel restrictions and crew quarantines, even getting the flight crew to Alice Springs is rarely simple. Our Flight Operations team has played a key role in making this happen. Often with the outbound flight crew being dropped off by diverting a regular cargo flight.

"It’s definitely a challenge, but there’s a huge sense of satisfaction when an aircraft departs Alice Springs and you receive feedback from the crew that the aircraft flew beautifully and had no issues,” says Ben.

At the peak of the pandemic, there were more than 70 Cathay Pacific aircraft parked in Alice Springs.

“To see all the aircraft tails glimmering in the desert is quite awe-inspiring,” says Ben. “But then when you think about impact of COVID-19 on us as an airline, it can be quite emotional. Particularly as engineers, we have a personal relationship with the aircraft and it does affect you.”

Thankfully, the peak of the pandemic appears to have passed, and today the teams are busy with reactivating rather than inducting aircraft. “Each aircraft returning to service is a step towards the recovery from the pandemic, which makes it all worthwhile,” adds Ben.

“The fact that we have weathered this storm together and we are still standing strong today has made me feel even prouder to be part of our airline,” says Pearl. In the not-too-distant future we hope to have the entire fleet back in the skies, leaving behind in Alice Springs fond memories of a challenge overcome.

How we’re flying

Learn how our employees made a difference for our customers and our communities.

-

What is the Closed Loop?

Read moreAll about the roster system that has seen our people spend up to 49 days away from loved ones.

-

Getting Fly Ready

Read moreHow one team created a new portal to help customers deal with an influx of new travel restrictions.

-

Proud to be flying

Read moreOne pilot reflects on why he was happy to be flying and helping serve the community.

-

Diary of a Closed Loop

Read moreOne Cathay Pacific pilot shares his diary of life inside the five-week Closed Loop system.

.renditionimage.450.225.jpg)